Fred Gardiner's Story

|

|

|

|

Text and photographs courtesy of Fred

Gardiner |

9/10th August 1943

Just before midnight on August 9th 1943, Lancaster W4236 'K' for King and dubbed

'King of the Air', was on course from base at Syerston near Newark, Nottinghamshire,

to Beachy Head and climbing to 18,000 feet on its last flight. The all-sergeant

crew, captained by pilot John Whitley and of which I was the wireless operator

was on its fifth mission, a raid on Mannheim in Southern Germany.

Just before midnight on August 9th 1943, Lancaster W4236 'K' for King and dubbed

'King of the Air', was on course from base at Syerston near Newark, Nottinghamshire,

to Beachy Head and climbing to 18,000 feet on its last flight. The all-sergeant

crew, captained by pilot John Whitley and of which I was the wireless operator

was on its fifth mission, a raid on Mannheim in Southern Germany.

Earlier that evening there occurred one or two incidents which would prove very

thought-provoking after this night. Back at base we had been through the usual

briefing procedures. My parachute was due for repacking and I had been given

a temporary replacement. Having handed in a nearly new 'chute this one looked

positively decrepit but one hoped it was not likely to be needed tonight (indeed

any night), and before the next operational flight my own new 'chute would be

available again.

After briefing we had time for a meal and a short rest. We shared a barrack

room with another crew. They were very new, in fact had arrived on 61 Squadron

only the day before. I was particularly pleased that the wireless operator was

an old friend, Stanley Banting from training course days (killed on a raid on

Leverkusen 22/23 August 1943).

His crew was not listed for this operation. They would have to make one or two

squadron training flights before going on the 'real thing' and so Stanley was

very interested as we prepared to leave. As my position in the aircraft was

served with warm air it was not necessary to wear special clothing unlike the

two airgunners. But I did prefer to wear my P.T. vest, which was longer and

of better quality than the standard issue of singlet. My shirt for the night

I noticed at the last minute had been badly torn by the laundry. In a weak attempt

at bravado I joked to Stanley that he could send a clean and newer garment out

to the P.O.W camp should we not return and even removed one from my locker and

hung it over the bed. It would be handy for tomorrow.

It was a warm and pleasant evening so the crews assembled at the appropriate

time on the grass in front of the flight offices. A local Home Guard platoon

had been invited to witness our departure and they mingled with us chatting

and sharing cigarettes.

Our crew of seven awaited the bus which would take us to our aircraft parked

on a dispersal point some distance away. In addition to pilot John Whitley who

lived with his parents and sister in a flat near Marble Arch, London, the crew

comprised Jack Kendall, tail gunner from Edmonton Canada, at twenty four the

oldest member; Peter Smith, navigator, from Woking, Surrey; Walter (Whiz) Walker,

bombaimer who came from Leeds; George Spriggs, whose home was in Braunstone,

Leicester, and myself from Banbury, Oxfordshire, all aged twenty or twenty-one.

Finally, at nineteen, Nevil Holmes from Whitstable, Kent, was the mid-upper

gunner. Also to go on board was a small cage containing a carrier pigeon. If

we had to ditch in the sea then at least here was another method of getting

a message to base. Last but not least, was Jack's mascot - a doll in the image

of Adolf Hitler, which would be hung by a string somewhere in the aircraft.

Whilst we were waiting Nevil insisted on checking and adjusting my parachute

harness . Previously I had been lax about this. I returned the favour.

The crew transports arrived and soon some dozen crews of 61 Squadron 5 Group,

Bomber Command were on their way to their aircraft. Syerston was shared by two

squadrons, No's 61 and 106, and in half an hour's time Lancasters of both units

would be thundering into the air at intervals of a minute or less. Our aircraft

was a veteran of seventy-six operational flights. Not yet having been alloted

a machine of our own we were 'borrowing' this one, its current regular crew

being on leave. On arrival at dispersal we were surprised to find two of these

crewmen out there awaiting us. This was the last day of their leave and they

were just a little concerned that another crew was being allowed to fly

their beloved 'K' for King. It had seen them safely through more than half of

the thirty 'ops' which would complete a 'tour' after which would follow a posting

for a rest on less hazardous duties. But concerned or not they wished us well,

their comment being "Bring it back please!".

At eleven forty-five we were airborne, carrying a four thousand pound high explosive

bomb or 'cookie' as they were popularly known, plus several thousand incendiary

bombs of various types and sizes. The route was out and back via southern England

to avoid the heavier defences of a shorter, direct one. At ten thousand

feet we switched on the oxygen supply.

From Beachy Head we turned on to a more easterly heading keeping a lookout to

avoid getting too close to others of the four hundred and fifty-seven Lancasters

and Halifaxes we were with. We were carrying (the first time for us) a device

code-named 'Monica'. This would detect another aircraft in the area up to a

few hundred yards behind us and set off a 'bleep' on our intercom. Half an hour

out from the English coast, at 18,000 feet and now over enemy-held territory

the bleep came on. Our tail gunner quickly reported that it was just another

Lancaster so we relaxed a little and eventually the signal ceased as the two

aircraft drifted further apart.

My job at this point was to tune my receiver to German fighter control frequencies.

On hearing German voices I was to jam them by transmitting the noise picked

up by a microphone in one of our engines. This technique was called 'tinselling'.

At regular intervals George Spriggs was pushing bundles of metallised strips

(code-named 'window') out of the aircraft through a special chute in order to

confuse the enemy radar operators.

At about this time Luftwaffe Leutnant Norbert Pietrek with his crew, Unteroffizieren

(sergeants) Paul Gartig (wireless/radar operator) and Otto Scherer (engineer/gunner)

was taking off from the German night-fighter base at Florennes, Southern Belgium.

Their aircraft, a twin-engined Messerschmitt 110F-4 armed with four machine

guns and two cannon was directed by their ground controller, Lt. Ernst Reith,

to patrol an area called 'Room 7B' around its base. A German account based on

crew reports continues:- "Expected altitude of approaching bombers was

6,000 metres. When the bombers came closer the communication failed and control

was almost nil due to the dropping of 'window'. The night-fighter was finally

given permission to leave its position and follow the bombers eastward. At 00.32

hours they found a bomber which was identified as a Lancaster. Pietrek opened

fire......"

At about this time Luftwaffe Leutnant Norbert Pietrek with his crew, Unteroffizieren

(sergeants) Paul Gartig (wireless/radar operator) and Otto Scherer (engineer/gunner)

was taking off from the German night-fighter base at Florennes, Southern Belgium.

Their aircraft, a twin-engined Messerschmitt 110F-4 armed with four machine

guns and two cannon was directed by their ground controller, Lt. Ernst Reith,

to patrol an area called 'Room 7B' around its base. A German account based on

crew reports continues:- "Expected altitude of approaching bombers was

6,000 metres. When the bombers came closer the communication failed and control

was almost nil due to the dropping of 'window'. The night-fighter was finally

given permission to leave its position and follow the bombers eastward. At 00.32

hours they found a bomber which was identified as a Lancaster. Pietrek opened

fire......"

The attack on our 'Lanc' came from astern and slightly below. Suddenly in a

few horrific seconds with no warning from 'Monica', the aircraft was filled

with flashes, bangs and the smell of cordite as the enemy gunfire ripped

through from end to end. Holes and torn metal appeared and I distinctly remember

our navigator still poring over his charts with tracer bullets passing under

his seat. John put the aircraft into a violent evasive turn, at the same time

Whiz Walker called on the intercomm. to Jack. Neither gunner had opened

fire and there was an ominous silence from the rear gun turret. Someone reported

an engine on fire. The fighter was difficult to shake off and the attack continued.

John called for the 'cookie' to be jettisoned, not only to lighten the aircraft

and improve manoeuverability but to remove the risk of the aircraft being blown

to pieces should it explode.

There was no time for the bomb doors to be opened and the bombs dropped by the

bombaimer from his instrument panel in the normal way. Also the complicated

release mechanism could well have been damaged. It was therefore my job to pull

the emergency handle situated in the floor a few feet behind my seat. This would

release the big bomb which would crash its way out through the closed bomb doors.

Every second counted. There was no time to disconnect the oxygen line and intercom

cord to my helmet so I discarded the lot, leapt over the main spar which formed

a back to my seat and gave a big heave on the handle.

The fuselage was now on fire, the flames appeared to be coming from the floor

on both sides of the aircraft. Could it be that our incendiary bombs, aligned

on each side of the four thousand pounder in the bomb bay below had ignited?

I was horrified to see flames surrounding the cases containing ten thousand

rounds of ammunition which was fed on tracks to the rear turret.

The inside of the aircraft was well lit by the flames and I saw that Nevil was

now leaving his turret amidships and making for the rear door which was our

emergency exit. The navigator had left his position and was going forward to

his exit down three steps to the front hatch. The captain must have given orders

to abandon ship but without a helmet and earphones I could not acknowledge.

To go back to my station and recover them was out of the question. The enemy

fighter was still firing on us from directly astern and tracer bullets, making

small points of light like glowing cigarette ends were flashing through the

fuselage.

I started to make my way aft to the rear exit, grabbing my parachute from the

rest bed. It had always seemed to me a better location, protected there

by a headrest of steel plate than in its official stowage - a plywood box at

floor level. I quickly snapped it on to the two hooks on the harness and continued

towards the rear door which was on the starboard side.

Nevil must have had some difficulty extricating himself from the mid turret;

one needed to be a contortionist to do so at the best of times, now with the

aircraft making violent manoeuvres it must have been particularly awkward, and

so I reached the door first. At that moment the aircraft performed such gyrations

that I was thrown from floor to roof and back to floor where it was impossible

to move. If at any time the thought "this is the end" entered my head

then this was the moment.

At the side of the door was a rack carrying thin metal dip-sticks to measure

the fuel in the aircraft's tanks. I managed to grab these and despite their

sharp edges was able to pull myself upright and grasp the door handle. At the

first attempt to open the door it reclosed on my thumb then suddenly it was

wide open.

We had made no parachute drops during training but had received instructions

on what to do should it be necessary. This advice now came sharply to mind:-

kneel on the door sill and roll out head first to avoid being struck by the

tailplane; wait until clear, not necessarily to the legendary count of ten,

then pull the ripcord. Looking astern I put my head out into the slipstream.

Perhaps a vacuum occurs across the face by doing this, in the event it was impossible

to breathe. Turning to face forward into air moving at over two hundred miles

an hour was also a startling experience, but this was no time to hesitate and

I rolled out, aware that Nevil was about to follow.

It took no courage to leave the inferno of 'K for King' which roared away into

the darkness. In a second or two it had gone. Completely disorientated I pulled

the ripcord - a metal handle on the 'chute; there was a violent jolt then utter

silence as I hung under the canopy in a clear sky. There was very little moon

but the sky above had the usual starlit glow. In one direction the horizon was

particularly bright, Mannheim under attack perhaps.

I was now aware of having bare feet. The jolt of the opening 'chute had removed

my wool-lined flying boots which had taken socks with them. How fortunate this

was a summer's night.

Where would I land? Looking down there was nothing but inky blackness contrasting

with the pale light of the night sky above. With eyes focused to see anything

that might be discernible several thousand feet below I struck the ground hands

and feet together with a thud which knocked me breathless. I had seen nothing

in the darkness and was quite unprepared for such a landing.

There was no wind and the 'chute collapsed gently over me. Extricating

myself I realised how fortunate I was to have landed on soft grass, in fact

the ground was rather soggy. But it had been a close thing, almost directly

above were power lines. The edge of the parachute may even have touched

them causing my landing on 'all fours'. A loud buzz denoted that the lines were

certainly 'live'.

There was nothing to do now except wait for daylight. Rolled up in the parachute

I lay contemplating my good - or bad - fortune and wondering the fate of my

crewmates. I felt a great feeling of thankfulness at still being alive. The

gunfire had missed me. The big bomb had not exploded before it could be released.

The aircraft had not blown up in the air. I had successfully jumped clear. The

elderly parachute had opened. The ground was soft to land upon. Fate had been

very kind to me, so far.

Ten minutes later in the night sky above, Leutnant Pietrek and his crew located

another bomber - this time Halifax HR872 from No. 405 Squadron flown by Canadian

F/Lt. Gray. It too was shot down by the Messerschmitt's machine guns, the cannons

having failed during the attack on our Lancaster. Of the seven crew of the Halifax

there were no survivors.

Top of page

10th August 1943

As dawn broke I could begin to see something of my surroundings.

On one side grassland with a boundary fence some fifty yards away, after which

the terrain fell away and I could see nothing beyond. On the other side a rough

stoney track ran alongside the pylons and disappeared between a few straggly

hedgerow bushes to right and left. Beyond the track more open scrubby grassland

with pine forest perhaps half a mile away making a backcloth in that direction.

A few noises, mainly of animals, - a cockerel, a dog, could now be heard in

the distance but there was no habitation to be seen. I examined myself for injuries;

sprained ankles but not painful enough to suggest broken bones; a sizable bruise,

almost from wrist to elbow on the right arm; cuts on the hands probably from

the dipsticks; a pinched thumb of which the nail was blackening, and a black

eye which would be more obvious in the next day or two. The opening parachute

had given me such a jolt that I felt slightly bruised about the ribs and for

a few days breathing was going to be noticeably painful. Overall the damage

seemed to be superficial, a fact for which I was very grateful.

Next to check was what equipment and useful articles I possessed. The 'chute

and harness were of no further use but the idea that the 'Mae West' lifejacket

would make some sort of footwear was not very successful. Before cutting it

up with a penknife I tried inflating it but the gas cartridge failed to work,

an incident to make me reflect on my good luck to be on dry land.

I had cigarettes and matches but my watch was missing, likewise my cap although

how the latter could have been ripped away from under a shoulder epaulette covered

by a lifejacket and 'chute harness was a mystery. A pity about the watch but

the lost cap was of no consequence. My escape pack was undamaged. I opened it

and transferred the contents to pockets. The pack contained Horlicks tablets,

chocolate, a tube of thick condensed milk, two silk maps the size of handkerchiefs,

a compass in the form of a marked button pivoting on another, and, in a separate

packet, Belgian and French banknotes to the value of about ten pounds. I also

had three passport size photographs for use on identity cards should there be

any chance of acquiring such items.

Where was I? That was the next most pressing question. I had seen the glow in

the sky which could have been Mannheim under attack but at what distance?. We

had been flying for an hour and a half at least. Studying the maps was not very

helpful. This could be Germany, perhaps Luxembourg, Belgium, or even France.

All these countries came together in this area. Pessimistically I concluded

it must be Germany, with luck it could be Luxembourg but in any case it was

now highly likely that I would be taken prisoner. The prospect did not daunt

me too much, anything after the experience of four hours ago would be an anti-climax.

Thought of being interrogated occurred to me, the possession of the identity

photos bothered me; would the Germans consider them the property of a potential

spy? Rather foolishly I destroyed them.

By now 'K for King' would be posted as "missing on operations". I

thought of those at home, my RAF friends and colleagues receiving the news,

and, later in the day that same news being received by my father and aunt at

Banbury, and other relatives and friends. They would be left wondering my fate

for some time to come. My fellow wireless op. Sgt. Stanley Banting would surely

be shaken by our failure to return after my jest of the evening before (in fact

Stan was posted 'missing believed killed' before my return to the UK and so

never learned of my survival).

Despite my predicament I felt a certain sense of relief that perhaps the war

was over for me and that my chances of seeing the end of it albeit as a prisoner

of war were now considerably better than they had been a few hours ago.

Of my crewmates, Jack Kendall in the rear turret must surely be dead, the others

would have had a reasonable chance of getting out but for the time being their

fates would remain unknown.

Having decided to make a move I caught the sound of a horse and cart on the

stoney track. Led by, presumably, a farm hand they came into view between the

bushes and stopped abruptly on seeing me. In some gesture of greeting (or perhaps

surrender!), I reached for a handkerchief to wave. The man must have thought

I was about to draw a gun, he took cover behind the cart! However, seeing I

was harmless and by now realising the situation he came forward. He shook

my hand warmly and pointed in the direction from which he had come using the

word 'camarade' which I showed I understood. He was soon on his way leaving

me to set off in bare feet on the sharp stones in the opposite direction. Progress

was painful.

I remained puzzled as to my whereabouts. The word 'camarade' sounded German

to me but this man with his friendly greeting could not possibly be German.

Perhaps he was a conscripted labourer or maybe this was Luxembourg after all.

The track passed under an iron railway arch and formed a T junction with a second

class road. A signpost opposite said 'RULLES' and pointed to the left. I could

see cottages a hundred yards or so in that direction and decided to make for

them. Smoke was coming from the chimney of one of the cottages on the right,

otherwise all was very quiet with no one to be seen. After all, it was still

a very early hour. The weather was fine with hardly a breeze.

I was within a few yards of the houses when I heard the sound of a motor vehicle

approaching from some way behind. Instantly it occurred to me that probably

only Germans would have fuel for cars or trucks. With the need to take cover

I ran to the house which had the smoking chimney. Throwing open the door I stepped

inside, closing it quickly behind me. From a curtained window alongside the

door I watched as a truck passed; it was a covered army vehicle, open to the

rear and sitting inside were soldiers, rifles between their knees. This

was the search party no doubt, but they had noticed nothing. For me it was my

first sight of 'the enemy'.

The stone floored room was austere to say the least. There was a table, a chair

or two, and a doorway leading to a back room. There were animals running about

in this back room, I seem to remember chickens included. So it was true that

country people on the Continent had their smaller farm animals in the house

with them! An elderly lady dressed in black was in the room. On seeing me she

burst into tears but whether from fright or pity was difficult to tell. A few

moments later a man of about forty came from the back room and greeted me enthusiastically.

He soon produced socks and boots and with an old black raincoat to cover my

uniform he indicated I should follow him. The language I had now concluded was

French. This did not completely solve the dilemma of my location but that it

was not Germany was at least a source of some comfort.

We left the cottage and crossing the road made our way to another, less obtrusive

from the highway and less austere than the first. Several people came to see

me. I felt rather like an object of curiosity; one elderly gentleman spoke a

little English. My uniform was changed for some very second-hand civilian clothes

whilst my new-found friends were obviously trying to work out a plan to get

me on to an escape route. A lady of about thirty whose name I learned later

was Madame Thèrèse Féry took a prominent part in the proceedings

and after some deliberation I was taken to a third cottage, even more isolated

and some way from the road. Here we were greeted by a man who at last cleared

up the mystery of my whereabouts by informing me "ici Belgique!".

I was welcomed into the house and was soon eating a slice from the biggest plum

pie I had ever seen and drinking what was perhaps a substitute for coffee. The

food situation however was really quite grim as I was going to discover.

At this cottage I remember being intrigued with the handpump at the kitchen

sink, the first time I had seen such an arrangement. During the afternoon a

doctor came to examine me. He was soon convinced that I had no serious injuries,

and handed me some banknotes before shaking hands and departing. Later in the

afternoon two young men arrived on bicycles. A third machine was found for me

and the three of us set off for a new destination.

Unlike Britain in wartime the signposts were still 'in situ' and so I was able

to make a mental note of place names, unfamiliar though they were. En route

one of my companions produced a black beret (every male member of the community

seemed to be wearing one), which fitted me perfectly. Judging from the reaction

of my friends I could now be taken to be one of them.

After a mile or so we arrived at a house in the little village of Marbehan.

We entered but there seemed to be no one about other than ourselves. My guides

however appeared to be quite familiar with the place and I was shown to a bedroom

upstairs where it was made clear I could spend the night. Left alone I sat by

the window looking out through the heavy net curtains; there was no one about,

these villages seemed almost devoid of inhabitants.

The elderly gentleman from Rulles came to see me. He was a little pessimistic

of my chances of escape. If I chose he would direct me to the gendarmerie where

I could give myself up, presumably in uniform again. But by now I was beginning

to think it might well be possible to get away and certainly worth a try with

or without the help of these sympathetic people. So I declined that suggestion

and left alone again began to feel the effect of no sleep for the past thirty-six

hours. Dusk was falling so I undressed and got into the not uncomfortable bed.

On the verge of sleep I was suddenly awakened by a small, rather sharp featured

man of about thirty-five. Monsieur Robert Féry, alias "Raymond",

was a man wanted by the Germans. He had apparently recently shot his way out

of a house where he was about to be arrested, killing several Germans. Now he

was telling me in words and signs that I was in the house of a collaborator

and we must leave at once. I dressed quickly and we were out of the house in

a few minutes leaving by a rear exit. Now it was dark and we left the road and

headed into the countryside.

We were soon on rough, undulating ground with stumps of trees in evidence. A

few words in a mixture of English and French from my companion told me that

this was a battlefield of the first world war. In the silence and in little

moonlight it was a somewhat eerie place.

My ankles were painful and breathing became a little uncomfortable as we walked

on for perhaps a couple of miles. Eventually we arrived at an isolated house

with a small front garden enclosed by a wall and wrought iron gates. A knock

on the door was answered by a priest who quickly ushered us inside. After some

conversation between the two men, M. Féry departed and I was left with

Monsieur L'Abbé Leon Chenôt, the rector of this tiny village of

Villers-sur-Semois.

From the hall of the house a door to the left opened into a large but rather

spartan dining room with scrubbed wooden-topped table. Here was L'Abbé's

housekeeper M'selle Gerlache, a middle aged lady whose face was very badly disfigured,

perhaps caused by a condition called Bell's palsy. I was given a warm welcome,

food and drink. By now desperately tired I was shown to a small bedroom upstairs

at the back of the house where I was soon asleep in a very soft bed.

11th August 1943 (Wednesday)

My benefactors allowed me to sleep on undisturbed through the

morning. A meal followed, of what it consisted is long since forgotten

among the many varied meals of the next few weeks. However, I well remember

the black bread, not quite so unpalatable as might be expected. The substitute

coffee (made from acorns so it was said) was a common feature of this part of

wartime Europe. It was rather bitter but one got used to it. Generally food

was scarce and I was conscious of being an extra mouth to feed. To say 'thank

you' seemed quite inadequate and was in any case waved aside.

After this particular meal, I was invited to relax in a small study across the

hall from the dining room. M. Chenôt told me (with some difficulty due

to the language problem), how on the previous night after twelve o'clock he

had been returning the few yards from his church to the house when he had heard

an explosion and seen our 'Lanc' coming down in flames.

He had a radio receiver secreted in his writing desk and he invited me to make

use of it but emphasised that the volume must be kept low. There was a penalty

for listening to 'enemy' broadcasts although it was not as stern as for harbouring

an escaping British airman, which could mean death or the concentration camp

- much the same thing. I was under no illusion of the risk these people were

taking.

It was here that I was shown a detailed map and was at last able to pinpoint

my location as being in south-eastern Belgium, not far from Luxembourg and the

French border. From the radio I learned that nine aircraft had failed to return

from the raid on Mannheim.

A motor cycle arrived at the front of the house and I was startled to see two

uniformed Belgian gendarmes approaching the front door. Before I could rnake

myself scarce they were being shown into the study by L'Abbé. My consternation

turned to relief and pleasure when they both saluted smartly and shook hands

with me in a most friendly manner. Neither could speak English but there was

no doubt they were delighted to meet me. One of them, Monsieur Remi Goffin,

I was to meet again.

During the evening M. Chenôt made me understand that I would be moving

on once more. When the time came to depart, rain was falling. The earlier acquired

raincoat had been left at a previous address but L'Abbé threw a cassock

around me and with the black beret I was well camouflaged for a night excursion.

By now it was almost dark, we walked for some minutes until arriving alongside

thick woods L'Abbé gave a low whistle. It was answered by someone in

the darkness. A man came forward whom I recognised as M. Féry. Wishing

us goodbye and good luck, L'Abbé turned for home. I could only thank

him heartily for his help and hospitality.

"Raymond" was armed with a pistol; there was one for me too. It was

loaded and I was shown how to release the safety catch if necessary. I was aghast

at the thought of having to use it, but could not very well back out of the

situation. Being now in civilian clothes, disguised as a clergyman and armed

made me realise that I was in a rather perilous position should we be caught.

Could I be accused of being an 'enemy agent' with all that implied?

The rain had now ceased, as we set off along a narrow road between the woodlands.

As there was a night curfew no one was supposed to be out of doors. Also M.

Féry indicated that we would have to pass through a military zone and

we must be as silent as possible. This man must have enjoyed danger. Could we

not have made a detour? Without a common language I was unable to put the question

to him.

After half an hour I sensed from "Raymond"'s increasing stealth that

we must be in the military area. Ahead of us and to the right was a typical

army hut. Suddenly the door was flung open, light streamed out, and German soldiers

emerged talking and laughing. M. Féry gave me a violent push into a ditch,

fortunately dry, at the road side. We crouched there without a sound as the

soldiers mounted cycles and rode off. Two of them came our way and passed within

three or four yards. "Raymond" had his gun trained on them until they

were well away from us. As they had just left a lighted room the soldiers could

probably not see well in the darkness, and in my ankle length black cassock

I must have been nearly invisible, but for us, eyes accustomed to the night

all was easily observed.

As the soldiers dispersed we moved on again and had no further frights. Another

kilometre or so and we came to Tintigny. Yet another small village it was

silent and dark. From the street we climbed some steps leading to the front

of a house at right angles to the road. M. Féry tapped lightly on the

door. We were quickly admitted into a pleasant sitting room where our hosts

were a man of perhaps sixty and, I presumed, his daughter, a young woman of

about twenty-five. There was much serious conversation between these two and

M. Féry, but as usual it meant nothing to me. I remember a sewing machine

on the table bearing the make name RAFF. Our host made some quip, pointing to

me and the machine which caused a little mild amusement. I was relieved to return

my gun to "Raymond". In no way did I wish to be involved in any future

shooting match. The cassock would be returned to L'Abbé.

As it was by now quite late we were shown to a room upstairs which M. Féry

and myself were to share for two nights. There was a bed fortunately large

enough for both of us but nothing else in the room except perhaps a small table

and chair. Our ablutions could be carried out in a large basement room, bare

of furniture with primitive toilet arrangements best described as a hole

in the floor. This was certainly austerity but hopefully we were safe here.

My companion did not venture outside, he was obviously hiding out like myself.

The time spent here was boring in the extreme. I do not remember seeing our

elderly host, and meals were brought to our room by the young woman. It was

almost a prison environment, with nothing to do, nothing to read, and no radio.

These people must have been living in very hard conditions but one could see

they were very proud and patriotic.

13th August 1943 (Thursday)

Very early in the morning of the second day at this address, M.

Féry made it clear that we would be moving on, some arrangements having

obviously been made. The sky was overcast and barely light as I said farewell

to our hosts. There was no mistaking their warm feeling for me, the young woman

kissed me on both cheeks with some emotion. No doubt they saw in me the evidence

that they still had allies carrying on the fight against the hated occupying

Germans.

After checking that all was clear, M. Féry escorted me a few yards to

crossroads which seemed to be the centre of the village. Although houses lined

the streets on all sides there was no one about until a car drew up alongside

us. M. Féry wished me a quick 'au revoir', and bundled me into the back

of the car. The driver, whom I learned later was the village physician, Doctor

Wavreil, indicated that I must lay on the floor and we drove off. Away from

the village the car stopped and waiting there was the gendarme Remi Goffin with

his motorcycle. I transferred to the pillion and we were off.

I remember an exhilarating ride along the narrow Belgian

roads, scattering chickens as we sped past little areas of habitation. The motorbike

went well on what must have been at least a proportion of paraffin judging by

the exhaust. After six or seven miles we approached a larger village and as

we entered I noted the name 'FLORENVILLE'. After Remi had made one or two enquiries

(there were a few people to be seen at last), we found a particular house near

the centre of the village where I was welcomed by Doctor Pierre. This was his

house and surgery. Remi Goffin did not stay longer than was necessary and I

was left alone in a room at the front of the house. The windows were tightly

closed as seemed to be common practice in Belgium, possibly against the flies

and I remember feeling hot and uncomfortable as the day had turned out to be

sunny and very warm. Refreshments or a meal must have been provided, probably

by the lady of the house, because it was dusk before Doctor Pierre himself returned.

He beckoned me to follow him and we left the house, keeping a distance of several

yards between us. As we walked past the quite sizable village square I remember

noticing the array of posts and poles (many of metal), carrying 'phone and power

lines. Insignificant perhaps, but like other unfamiliar features in these foreign

surroundings, it was another reminder of the unusual predicament in which I

now found myself. Taking one of the several roads leading from the square we

were soon passing rather larger and more substantial houses than I had noticed

in the previous villages. Half a mile from the square we stopped at one on the

left and Dr. Pierre cautiously made his way around the flower beds of the large

front garden to tap gently on one of the windows. The door was opened and we

entered.

"Welcome to my house" were the first words spoken

to me by Monsieur Charles Spruyt. Charles was stocky, ruddy complexioned, and

aged something over fifty. It was a relief to find someone at last who

could speak fluent English. With M. Spruyt (pronounced Sprate I was told), was

his wife Genevieve (whom I was to call Madame Giny) and their eighteen

year old daughter Charlotte whose name was always shortened to Lolotte. After

the very warm and friendly introductions, Dr. Pierre left and the evening was

spent in much conversation with Charles being kept exceedingly busy as

interpreter. Madame Giny, an attractive and vivacious lady, was most talkative;

she spoke only French but I had never heard anyone speak any language so fast.

I could understand not a word, but it was a pleasure to talk with Charles after

three days of mostly sign language. I was given the best bedroom for my first

night here but subsequently was transferred to the 'room in the roof'.

"La Sapinière" was a sizable detached house of some character.

At the front, a flight of steps with balustrades led up to the glazed wide door

and a rail to right and left enclosed a veranda. The large square garden, in

addition to flower beds had shrubs and pine trees which gave the house its name.

From the central tiled hallway was a dining room to the left with large kitchen

leading off. On the right from the hallway was a pleasant lounge with a dividing

screen and amongst the substantial pieces of furniture was a piano and large

portrait paintings of forebears of the family. A glass fronted bookcase

had been struck by a bullet during the German advance in 1940 and still bore

the scars. All the rooms had high ceilings, and with many windows, all with

shutters, the house gave a feeling of spaciousness and luxury.

Before the first world war, Charles had worked in a London office, which explained

his good English. Then, as a Belgian soldier, he had served alongside British

units. He held the British in great regard and I am sure he thought it an honour

to give shelter to a British airman. His business was in the insurance

world but doubtless the occupation of his country had had an adverse effect

on such a business. I regarded him as being typical of a retired country gentleman

of reasonable means. The family was able to obtain items of food including eggs,

meat, and the scarcer vegetables and fruit from the local farms, a black market

in fact denied to city dwellers and the less well-off. Meals were served in

some style appropriate to the status of the family and I was treated as one

of them and with the greatest generosity. Each day there was a packet of expensive

Turkish cigarettes. That they were available was a surprise to me, but the local

ones in cheap paper packs and labelled "VF" which I translated as

'Very Foul', were just that. Also I was supplied with my own toilet articles,

a new shirt, cotton pullover, and for future travelling, a small haversack.

All of these must have been very scarce and expensive at that time in a country

denuded of consumer goods.

For transport everyone had a bicycle. It was strange for me to see that the

cycles were registered and had to carry number plates. All three members of

the family would make frequent journeys to the farm and shops and Charles always

wore a 'plus-fours' suit, very sensible attire for cycling. This made him look

even more the 'country gentleman' .

On the second day a man obviously with active connections with the Resistance

movement arrived to see me. He asked questions designed to test my authenticity.

It was known that the Germans had introduced their own English speaking agents

as RAF men on the run in order to expose and destroy the escape lines which

were being formed. During our conversation he suddenly gave me a sharp punch

to the body, then with a smile explained that it was a test to see if my response

would be an exclamation in German! I was so non-plussed that I had not even

exclaimed in English. Next, a head and shoulders photo was taken for use

on an identity card. To admit to destroying copies of my own passport photos

was too embarrassing so I did not mention it. As it was, the locally taken photograph

clearly recorded the unmistakable black eye.

My room in the attic was pleasant and comfortable and included a water jug and

basin (surprisingly the house had no bathroom) and there was a small window

which gave a look-out from the end of the house. I was to spend two weeks at

"La Sapiniere", Avenue de la Gare, Florenville. A cleaning lady came

each morning. Her domain did not include the attic and she was not told of my

presence and so I had to remain quietly in my room until she had finished her

work. Only after the war did she learn of my existence, much to her astonishment.

Occasionally I would venture into the garden but kept a wary eye on passers-by.

Charles had told me that a small detachment of German military police was stationed

in the village and we were all sitting on the veranda enjoying a warm evening

when two of them passed the house. For a few minutes the conversation remained

strictly French.

As well as listening to the. BBC, Charles was also breaking regulations by rearing

a pig in a shed at the back of the house. With mischievous humour he told me

its name was Fritz. The electricity supply was very erratic. The lights would

frequently dim and brighten but apart from lights and radio there was no other

electrical equipment to be affected, the days of the refrigerator and washing

machine for everyone, not to mention TV, were some way off.

Each day after breakfast I would retire to my attic room and spend some of the

time reading the two English books the Spruyt family possessed, "Little

Lord Fauntleroy" and Dickens' "The Old Curiosity Shop". The rest

of the day I was free to use the downstairs rooms, but had to take care to avoid

being seen at the windows. Playing the piano (quietly, and within my limited

capability) also provided a pastime. Nevertheless there was plenty of time to

speculate on my chance of returning home safely. It was a daunting prospect;

the way out was the walk over the Pyrenees, the whole length of France away.

Alternatively there was the well-guarded border to cross into Switzerland, which

meant internment until the end of the war, as yet nowhere in sight. To escape

across the Channel was out of the question. As a crew under training we had

been given one or two talks on evading capture should we be shot down. Although

everyone listened intently to the speakers (one of whom had gone through the

experience) it was something one couldn't easily visualise happening to

oneself; yet here was I now in that exact situation. It produced a feeling almost

of incredulity.

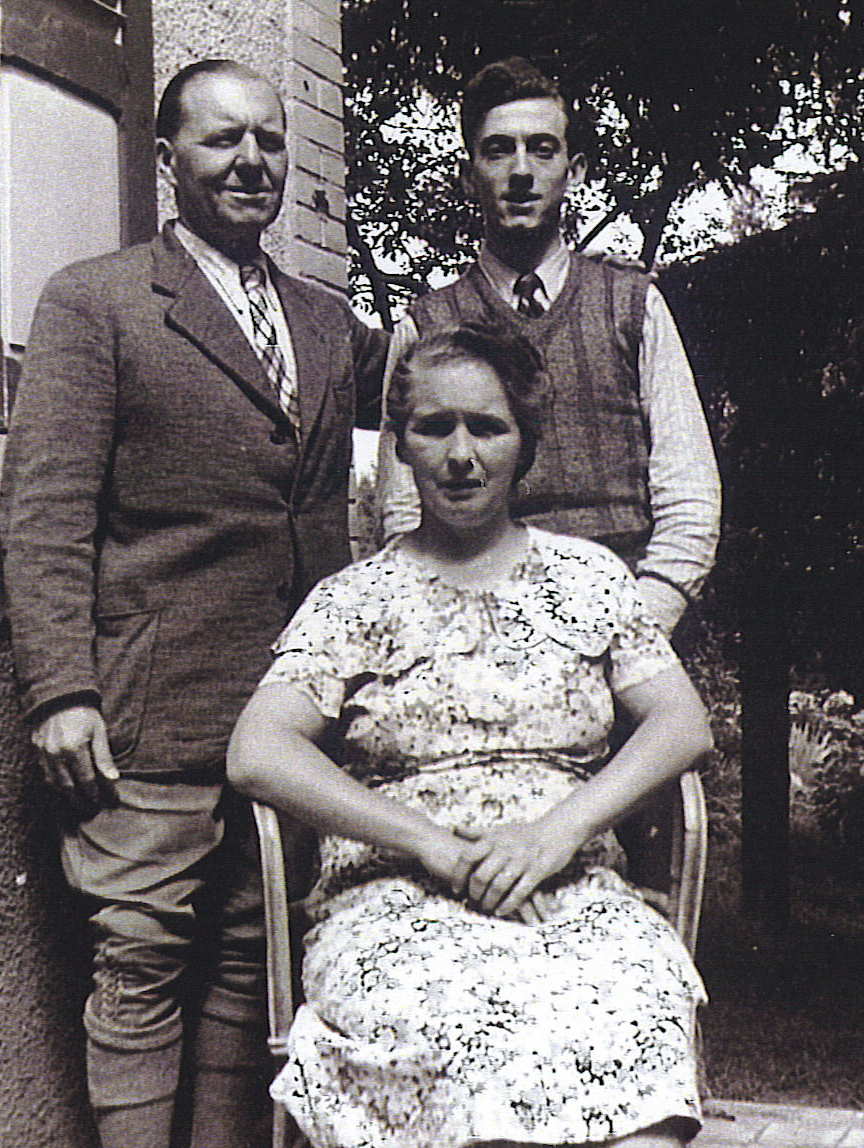

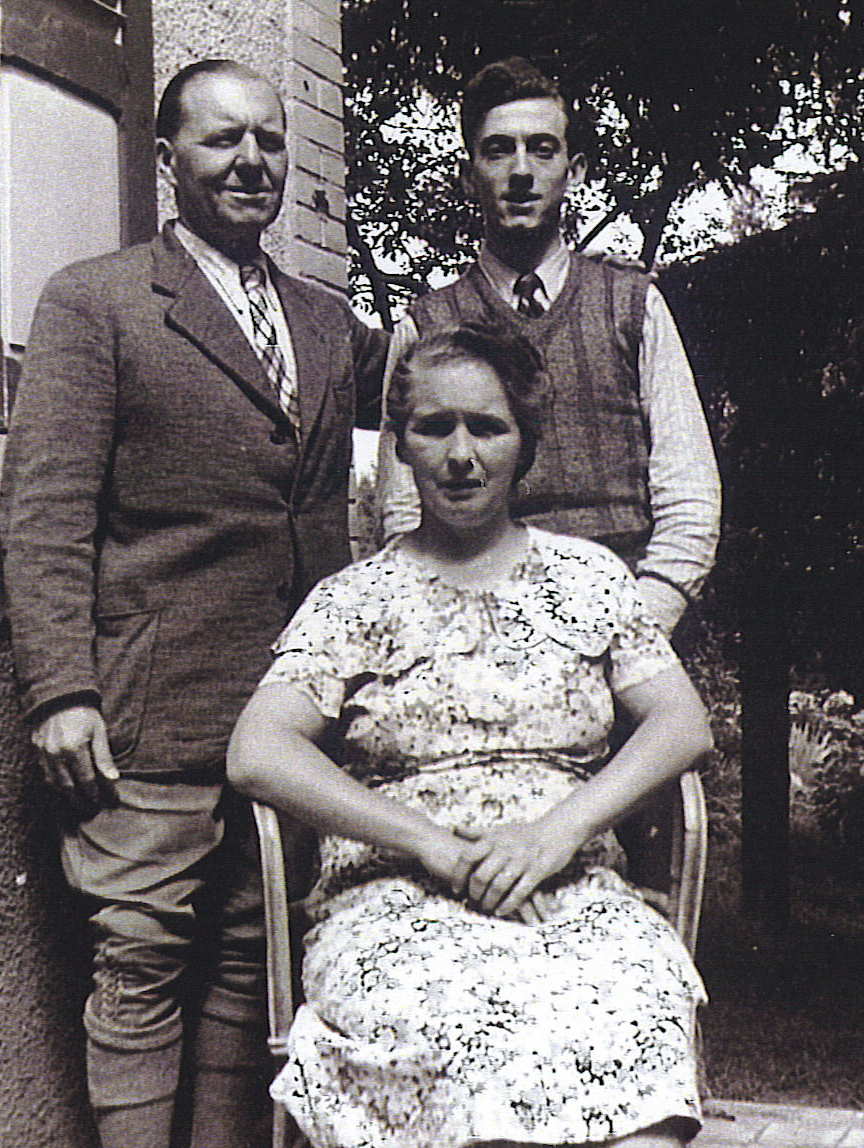

M. and Mme. Spruyt received several visitors during my stay. Some, obviously

were not to be told about the foreign guest and then I would be shepherded quickly

and quietly out of sight. But I was introduced to one or two of them, in particular

to Madame Giny's sister, Mme. Cornet and her husband who took photographs of

myself with the family and made a great fuss of me to my embarrassment.

One

day my inquisitor of the Resistance returned. He had an identity card for me,

a good forgery, on which I was named as Jean Joseph Jacques, a farm worker from

the village of Hachy. The 'official' stamp was rather blurred but at least it

was a document to produce should I be challenged. The prospect of being picked

up by the Germans did not however become any less alarming. Madame Giny, on

laundering my underwear was horrified to notice my name, number and rank

clearly labelling my PT vest. The only way to remove it was with scissors after

which a very neat darn by my hostess repaired the hole. The vest complete with

darn still exists more than fifty years later.

One

day my inquisitor of the Resistance returned. He had an identity card for me,

a good forgery, on which I was named as Jean Joseph Jacques, a farm worker from

the village of Hachy. The 'official' stamp was rather blurred but at least it

was a document to produce should I be challenged. The prospect of being picked

up by the Germans did not however become any less alarming. Madame Giny, on

laundering my underwear was horrified to notice my name, number and rank

clearly labelling my PT vest. The only way to remove it was with scissors after

which a very neat darn by my hostess repaired the hole. The vest complete with

darn still exists more than fifty years later.

26th August 1943

It was time once more to move on. In the morning my new haversack was packed,

Madame Giny making sure I had plenty of sandwiches. Then Charles and Lolotte

pushing their bicycles accompanied me back to the village square where we took

a road leading away in the opposite direction. Again there were few people and

no traffic to be seen. Half a mile from the village we halted and rested on

the grass verge. Two German military policemen cycled by but gave us no more

than a glance. After a short wait a motorcyclist approached from the village.

It was Dr. Pierre who was to take me to my next destination. With farewells

and good wishes from Charles and Lolotte and some regrets I was off again. Not

a long journey, perhaps four or five miles and we arrived at Muno, another village

in the chain.

Doctor Pierre delivered me to a house with a small front garden and opposite

the Gendarmerie. This was the home of the burgomaster, Monsieur Joseph Godfrin

whom I saw but briefly before being taken through the house to a conservatory

at the rear. For several hours I sat here alone and, well I remember, without

a cigarette. At dusk a youth and a girl, both about sixteen appeared. Leaving

with them I was taken a few hundred yards out of the village to an isolated

house laying back some fifty yards from the road. Here I was to spend the night

in a room with only a skylight in the ceiling, but it was comfortable and I

slept well.

27th August 1943

Breakfast was served on a large table by the window in the front

of the house and shared with three or four members of this household whose names

I never learned. The only other feature of this place that I can recall was

the outdoor lavatory. Typically rural with wooden top and front, lifting the

lid revealed a drop of twenty or thirty feet to an underground stream, a convenience

in every sense.

After breakfast my two young friends of yesterday re-appeared. They and the

others were perturbed about the strips of 'window' littering the landscape.

I was able to reassure them that they were not poisonous or harmful in any way,

but with the language problem and their ignorance of radar it was impossible

to enlighten them as to its true purpose. They settled for an explanation that

it interfered with the radio.

We now returned to M. Godfrin's house, where once again I found myself alone.

However, after only an hour or so two ladies appeared, one presumably Mme. Godfrin,

the other being introduced to me as Mme. Alice. They were sisters and Madame

Alice was to be my guide on the next stage of the journey. There was indeed

some urgency to get away, the Germans were suspicious of M. Godfrin and we could

possibly be raided. This house was in fact a link in the 'Possum' escape line.

We set off on bicycles. The weather was fine and very warm and the eight or

nine mile journey was hard work for Madame Alice, a rather plump lady of perhaps

forty. The ride itself was through the delightful forest region of the Ardennes,

along narrow roads sometimes no more than tracks. It was evident we were keeping

away from main thoroughfares for obvious reasons, and for the first few miles

saw no one. Eventually we joined a main road but again there was virtually no

traffic, the occupation seemed to have immobilised the whole country.

I was aware that we were now approaching a town, but suddenly we made a sharp

right turn off the road on to a narrow rough track which all but terminated

after a hundred yards or so. Here on the left and after passing one or two windowless

brick buildings, we arrived at a cottage situated side-on to the lane. The front

of the house looked down the flat valley of the river Semois which flowed fast

and wide some thirty yards away. From the edge of the far side of the river

the terrain rose steeply and was densely tree covered, the whole area well qualifying

as a beauty spot. The only man-made construction in this scene was a large tobacco

drying shed situated about a hundred yards in front of the house and surrounded

as one would expect by the growing plants.

We entered the house by the front door (there seemed to be no other entrance)

and were welcomed by the occupants. They were Monsieur and Madame Pierret, a

middle aged couple, typical workers of the land, and a somewhat younger woman

whose name was Madame Simon. There was also an elderly lady, perhaps a parent

of one of the others whose name I never knew. Once more I sat aside while a

great deal of conversation went on in French. Madame Alice had brought

knitting and wool. She unwound a ball of wool to reveal a handstamp, perhaps

the one used for my identity card and now being passed on for further use. My

new hosts provided food; I remember waffles with jam was a favourite in this

household, and after a meal we said goodbye to Madame Alice.

Here I was to spend the next fourteen days. The house had three storeys and

I was given a small cosy room on the top floor. It had a low ceiling and a window

overlooking the track down which I had cycled. There were several small doors

enclosing shallow cupboards on the walls. My curiosity led me to open them -

they were packed tightly with cigars, undoubtedly the produce of this tobacco

farm. My bed was very comfortable with an immensely thick duvet.

Unfortunately none of these people spoke English. I was learning a few words

of French but in no way did it allow real conversation. M. Pierret was busy

most of the day attending to the crops (there was a small orchard as well as

an acre or two of tobacco), looking after five or six sheep in pens at the side

of the house and sometimes fishing. I accompanied him on these occasions and

we sat together on the river bank smoking either VF's or cigars but unable to

make much conversation. The results of the fishing were not particularly impressive.

A somewhat solemn man, M. Pierret portrayed a rather unkempt figure, often unshaven,

with drooping moustache and always wearing his large cap. His wife, a tall,

rather plain, boisterous woman was less untidy, while Madame Simon was small,

dressed in black with long skirts, perhaps to cover a deformity as she had a

pronounced limp. Her husband, a Belgian soldier, was a prisoner of war in Germany.

They were all living for the day when, as they told me "the British soldiers

would arrive," and even pointed out the direction from which they would

come - from the west no doubt, through the orchard! What a pity I thought much

later, that it was the Americans who liberated this area.

This place was so well away from the beaten track that I remember only two visitors

during the whole fortnight of my stay. Although it would have been foolish to

wander too far, I spent many hours along the river bank and walking about the

valley. Rarely would there be anyone walking on the opposite bank but the river

was sufficiently wide to prevent any form of communication; this then was a

good 'hide-out'.

One day the two young people from Muno called and ran excitedly across to where

I was strolling among the tobacco plants. They had startling news; the burgomaster's

house had indeed been raided by the Gestapo only hours after my departure but

fortunately M. Godfrin had been forewarned and by now should be safe in Switzerland.

There was no other excitement during my stay at 'Au Maqua' but one night I was

awakened by the roar of aircraft as RAF bombers flew overhead on their way to

some target in southern Germany. The noise continued for more than half an hour.

I got out of bed and sat by the open window to listen; my thoughts being very

much with my erstwhile comrades in the darkness above.

Meals at 'Au Maqua' were rather less formal than at 'La Sapiniere' but were

adequate nevertheless. Amongst the fare was milk from the sheep, which although

looking richer than cows' milk, was agreeably very similar. One disagreeable

feature of life here was the multitude of house-flies, at mealtimes they were

particularly abnoxious, and apart from beating at them with anything that could

be used as a fly-swat there was no cure. The weather during all this time remained

fine and very warm and it was almost possible to imagine that one was on holiday.

10th September 1943

Eventually the time came to move on. Somehow a message was received that a car

would collect me during the morning and so when it arrived at about 11.00 a.m.

on Friday 10th I was ready and waiting. After fond farewells to the kindly

people of 'Au Maqua' I found myself being driven away in a taxi, my escort this

time, in addition to the driver, was a tall man who was in fact the husband

of Madame Alice. We turned towards the town I had fleetingly seen two weeks

before. It was Bouillon, a place with lots of history and a famous castle. The

taxi pulled up in front of a hotel in one of the main streets and we quickly

entered and made our way to a back room which had evidently been booked for

the occasion. Two or three other men were in the room, seated at a large table

which was laid for lunch. We joined them and the door was locked. After much

shaking of hands, I was delighted to find that the youngest man present, apart

from myself, was Flight Sergeant Herbert Pond of the Royal New Zealand Air Force.

It might be interesting to briefly relate his story. He was the pilot of a Lancaster

'pathfinder' which crashed in Belgium. After being attacked by fighters he dived

in an effort to shake off the attackers. Damaged, the aircraft literally flew

into and along the ground, killing at least one crew member. The survivors spilled

out from the wrecked aircraft and scattered in all directions fearing fire or

an explosion. In the darkness they had become permanently separated. Herbert

Pond had not seen any of his crew since then. It was gratifying to think

that from now on, I would have a compatriot to share whatever was in store for

us. Moreover to talk freely in English again (even in low tones) was marvellous.

It might be interesting to briefly relate his story. He was the pilot of a Lancaster

'pathfinder' which crashed in Belgium. After being attacked by fighters he dived

in an effort to shake off the attackers. Damaged, the aircraft literally flew

into and along the ground, killing at least one crew member. The survivors spilled

out from the wrecked aircraft and scattered in all directions fearing fire or

an explosion. In the darkness they had become permanently separated. Herbert

Pond had not seen any of his crew since then. It was gratifying to think

that from now on, I would have a compatriot to share whatever was in store for

us. Moreover to talk freely in English again (even in low tones) was marvellous.

Flight Sergeant Pond was however in some trouble. Due to confusion on the radio

link with London, the Resistance suspected that he was a German 'plant'. One

of our party spoke some English and asked me if I could vouch for him. By questioning

Herbert it transpired that he and I had been on overlapping courses at our OTU

(Operational Training Unit) at Cottesmore, Rutland, earlier in the year. He

remembered and described an occasion there when Australian crews 'acquired'

live chickens and engaged in hen racing across the parade ground. Such a bizarre

event (which I too remembered well) would hardly have been known in such detail

by an infiltrator and Herbert was exonerated. Afterwards he said that I had

saved his life, such had been the suspicion in which he was held.

That lunch in the Hotel de Progress, Bouillon, seemed particularly good, almost

like a celebration. After the 'coffee' and cigars, the door was unlocked and

a surveillance of the street was made. Then Herbert and myself with Monsieur

Arnould (Madame Alice's husband) reboarded the taxi and we were off once more.

We were now to cross the border into France. At a convenient and quiet spot

the taxi stopped and the three of us alighted. A young woman, who must

have been awaiting our arrival, now appeared and escorted us into the thick

woods bordering the road. The taxi driver would take his vehicle through the

frontier barrier in the authorised manner while we were to cross unseen (we

hoped) through the woods. After ten minutes or so of walking we arrived at a

small building almost completely surrounded by the trees. Clambering down a

slope, we entered via a back door which led into a tiny bar, almost English

style. We were provided with drinks and although those present may have been

aware of what was going on, Herbert and I stayed mute. We were now in France,

at the Café aux Chapelle.

Here M. Arnould suggested we hand over our Belgian money to him. This did not

seem to be unreasonable in view of the expenses being incurred, moreover

the money was now of little use this side of the border. I learned later that

the taxi driver was upset at not receiving a share towards his costs.

At this point we acquired a new guide whose name remains unknown. This man spoke

some English and we were able to converse a little with him while M. Arnould

made his farewell, presumably to return across the border. Soon the taxi appeared

in the narrow road in front of the building and with our new guide we climbed

aboard and resumed the journey. The situation was now to change dramatically.

From seeing so few people during the past month, we drove into the French border

town of Sedan which was a comparative hive of activity. The taxi pulled up in

the precincts of the railway station. There were German soldiers everywhere.

After a brief 'au revoir' to our driver, who stopped barely long enough for

us to alight, our guide led us to an unoccupied bench-type table and obtained

refreshments from a nearby kiosk. He then left us for a few minutes to

buy rail tickets. We were now joined by several German soldiers who leaned their

rifles against the table whilst they drank their beer.

To jump up and make off immediately was obviously not the best thing to do,

so we sat still and unspeaking. The situation was eased a minute or two later

by our guide who returned, and speaking a few words of French made it quite

clear it was time to go. Handing us our tickets we passed through the gates

on to the station. I was gaining some confidence by now and even risked

a 'merci' to the ticket inspector. On a quiet part of the platform Herbert and

I were briefed as to what we were to do next. Our tickets were for Reims; we

would board the train separately. At our destination we would be met at the

station exit by a woman dressed in black and with a floral buttonhole. We were

to follow her, keeping at least ten metres apart.

The train drew in and suddenly I was on my own. The coaches were corridor type

and the train stopped with a door opposite to me. I made for the steps whereupon

a French porter shouted at me, waved his arms and pointed to a notice, of which

there was one in every compartment window near me saying "Reserve pour

les troops d'occupation". Even I could understand that, but then I noticed

that civilians were standing in the corridor. Ignoring the porter, I climbed

aboard and took up a position midway along the coach. The compartments had been

unoccupied, now they were quickly filled with soldiers. My carriage took on

army and airforce officers in their resplendent uniforms displaying German crosses

and swastikas in profusion. It was difficult not to stare, but I flattened myself

against the side of the corridor while several of them squeezed past, one or

two even giving me a curt 'pardon'. How ridiculous, I thought, that German officers

were being polite to me in French. If only they knew that this fellow traveller

was wearing an RAF PT vest..…!

In addition to the Wehrmacht and the Luftwaffe, a contingent of Red Cross nurses

was boarding the next two or three carriages. All the Germans looked very smart

in contrast to the outnumbered and shabbily dressed civilians. The train was

quite full by the time we pulled out of the station. There was no sign of Herbert

Pond; he boasted later that he spent the journey in the buffet car where someone

bought him a drink. At Charleville we stopped, the engine was transferred to

the opposite end of the train and we drew out in the direction from which we

had arrived. The scenery was uninteresting and after a journey of perhaps one

and a half hours we pulled into Reims station.

Here the plan went like clockwork. Herbert reappeared on the scene and we were

soon following instructions to the letter. The lady was waiting at the station

exit. Across the square in front of the magnificent cathedral and into

one of the main streets, I kept a close watch on both our guide and Herbert.

Presently we found ourselves in a smart flat on the first floor above shops.

But this was a very temporary refuge, and after no more than an hour we

were escorted again to a new address a few streets away in a quieter part of

the city. Here were several members of the household including an elderly man,

partially blind, who was continually being scolded by the others for listening

to the BBC's French broadcasts with the volume dangerously high. Herbert and

I were given a pleasant room in the style of a 'bed-sit' with twin beds, but

it was to be for only one night.

During our brief visit to Reims, I asked the names and addresses of our benefactors,

but as it would have been very unwise to have any written material on one's

person, this had to be committed to memory. Our French friends were taking no

chances and many years later I learned that even these addresses were bogus.

That of the smart flat was subsequently found to be non-existent. The house,

we understood, was No. 4, Rue de la Liberté, but post-war enquiries revealed

that we stayed, in fact, at No. 51, Rue Battesti, the home of Madame Bulart,

a middle aged lady and her family. Such were the ruses deployed by the Resistance.

The blind man was Monsieur Drion whose family was also involved in the Reims

activities.

Madame Bulart asked me to write to her sister, Mrs. Gray, who lived in Gainsborough,

Lincolnshire, should I reach home safely. The address, 15, Limetree avenue,

was memorised. Mrs. Gray was to be told that the family, although living under

difficult conditions, was well. I was able to carry out this small service sooner

than I could have imagined at the time.

11th September 1943

In the early afternoon Herbert and I were visited by a suave, well-dressed

Frenchman who spoke fluent English. He would accompany us on the next leg of

the journey. We were soon back at Reims station where tickets were bought and

where I remember a Dornier bomber circling overhead as we waited for our

train. The local train pulled into a siding and the three of us boarded. This

was definitely third class travel - wooden slatted seats facing each other across

cramped compartments and with no corridor. The train filled up rapidly, our

fellow passengers, mostly women, seemed to be local country people returning

home from a trip to the city. Despite the fact that we never spoke for the whole

journey of perhaps forty minutes, this did not seem to attract attention, and

although friendly glances were exchanged, no one attempted to speak to us which

was a relief.

We left the train at Fismes, a small town according to the map, but we saw little

of it as our guide, led us to a house only a few minutes walk away. Our Frenchman,

(he may in fact have been French Canadian) I surmised was rather more than just

a patriotic helper. As if to confirm my view, he produced his identity card,

the photo of which he explained had been taken in London the previous week.

Our accomodation at Fismes was in a fair-sized end-of-terrace house with three

or four occupants whose family name, Beuré, I did not learn until many

years later. One of them showed us a dismantled 'Flying Flea', a small home-built

aeroplane popular in the nineteen-thirties but considered dangerous to

fly. This was stored in a barn, one of several outbuildings at the side of the

house. The owner must have been joking when he remarked that as a last resort

one of them might get to England in it! Once more Herbert and I were given a

comfortable room to share and were provided with cigarettes and a copious supply

of white wine. The windows were heavily curtained, we could hardly see out let

alone anyone see in, so we felt fairly secure. I remember being asked not to

disturb the spider in the outside toilet. Such a mysterious request had to be

investigated! The creature was immense with a huge web; its duty was obvious

and very effective.

The French (or Canadian) agent, who had brought us to Fismes, now had some remarkable

and exciting news. It might be possible for Herbert and me to be flown out of

France by an RAF 'plane which was expected to bring supplies in for the Resistance

during darkness. This might be tomorrow, weather and moon permitting, but we

would be kept informed. However, we were disappointed when, by the afternoon

of the second day we learned that the operation was 'off'. There had been rumours

back on the squadron that the RAF were operating in and out of France by night,

carrying agents and equipment as well as dropping people and supplies by parachute.

The rumours then were true.

Top of page

13th September 1943

In the afternoon Herbert and I were alerted for a possible rendezvous with

the aircraft that night. As darkness fell, our small party - including three

or four members of the Resistance, set off under a bright moon through the silent

countryside in single file and with no talking allowed. How far we walked is

difficult to recall, three or four miles at least, but we had not reached the

landing site when the aircraft arrived overhead, circled and flashed its identification

light. We began to run whilst the 'plane made several circuits, occasionally

going out of earshot. This activity must be alerting every German soldier for

miles around, were my thoughts, as we ran on, the silence being shattered by

the noise from the aircraft's engine each time it flew overhead at a few hundred

feet. Then, consternation when, on reaching the landing field we found that

most of it had been ploughed, leaving only a strip of grass with a haystack

at the end. Would such a restricted landing area be adequate? Torches attached

to sticks were quickly set out as markers for the pilot, and it was my job to

flash the letter 'R' as a 'safe to land' signal.

The aircraft came in over the haystack and landed with a considerable bounce

a few yards in front of us, then quickly came to a stop and taxied back to our

party. The engine had to be kept running - it seemed deafening - and I half

expected the enemy to rush out from all sides. The aircraft was a Lysander of

No. 161 SOE (Special Operations Executive) Squadron, piloted (I learned later)

by Squadron Leader Hugh Verity whose book "We Landed by Moonlight"

records this operation among the many others he successfully completed. The

Lysander was a single engined, high wing monoplane, which could fly slowly and

land and take off in short distances. This one had a large torpedo shaped long

range fuel tank under the fuselage, and a fixed ladder to the rear cockpit on

the port side. I had been instructed to remove parcels from this cockpit, take

my place there and operate the intercom to advise the pilot when all was ready

for take-off. Flight/Sgt Pond and an agent codenamed 'Grand Pierre' quickly

followed me aboard. There was very little room in the cockpit designed presumably

for one person but we closed the perspex cover and sat huddled on the floor.

If there was a seat, I certainly did not get the benefit of it; also there were

no parachutes, a disconcerting feature.

We flew back in bright moonlight at perhaps four or five thousand feet. There

was no cloud and the ground could be seen clearly. At the coast, a few searchlights

were evident but made no attempt to pick us up. Across the Channel and just

off the English coast, I was able to identify Brighton and soon we were coming

in to a smooth landing at Tangmere near Chichester. 'Grand Pierre' was whisked

away in a car while Herbert and myself were taken to the special quarters of

161 Squadron. There, after expressing our admiration and thanks to Squadron

Leader Verity, we were given a meal and quarters for the remainder of the night.

14th September 1943

In the morning, we were taken by car to the Air Ministry in London where our

absence would have to be explained. Five weeks back pay plus a month's leave

was to be some compensation for the 'inconveniences' suffered. Early in 1944

a German communiqué gave my name, number and rank as being an enemy airman

"at large on the Continent of Europe". As a result, I would not be

sent on operations over Europe again.

Top of page

Sequel

Of our crew, the two air-gunners, Nevil Holmes and Jack Kendall, as well as

flight-engineer George Spriggs lost their lives that night in August 1943. From

Belgian accounts, it seems that the Lancaster blew up just before hitting the

ground outside the village of Marbehan. Jack was thrown from the aircraft; his

body was found in the morning alongside the fence bordering a road, but he had

probably been killed in the initial attack. The bulk of the aircraft crashed

in a nearby field, some of the debris falling on the village although no damage

or injuries were recorded there. As for Nevil and George, no one knows

exactly how they died, and unfortunately my hopes for Nevil had been unfounded.

For George, it was ironic that he should die in an aircraft which he had serviced

and remembered well, from his days as a ground engineer, before volunteering

for flying duties. He had been delighted when, on completion of training we

had been posted to his old squadron. The three are buried at Florennes near

the enemy fighters' base in Belgium.

John Whitley and 'Whiz' Walker (who were both helped by the Féry family),

made contact and together journeyed to Switzerland, where they crossed the border

on Christmas Eve 1943 and were interned. Navigator Peter Smith saw the wreck

of our 'Lanc' from a train on his travels to Brussels, before going on to Paris

and the south of France on the famous 'Comete' escape line. He eventually crossed

the Pyrenees on foot and was imprisoned by the Spaniards. Later he was freed

after representations by the British Consul and reached home via Gibraltar.

I met my surviving crewmates again; John and Peter by arrangement and 'Whiz'

by sheer chance on Sheffield railway station some two years later.

On subsequent visits to Belgium, being treated with the greatest hospitality

by Monsieur and Madame Spruyt at 'La Sapiniere' and, later by their daughter

Lolotte and her husband Rene Zimmer, I met again many of my helpers. How some

were located again makes another story. They included Robert Féry and

his wife Thèrèse; the old gentleman from Marbehan; Doctor

Pierre; L'Abbe Chenôt and Mlle. Gerlache; M. and Mme. Pierret of 'Au Maqua'

with Mme. Simon and her husband safely returned from Germany; M. Godfrin, and

Madame Alice Arnould. Later I learned that my friends at Tintigny had indeed

been father and daughter - M. and Mlle. Pauly, and I met again the taxi driver

M. Paul Frerlet. They all had their own story to tell. Madame Féry was

shot and wounded on being arrested for activities fortunately not related to

my escape. Paul Frerlet had taken twenty-two airmen (British and American) as

well as political refugees from Belgium to France, and both these brave people

had spent several months in concentration camps suffering horrific treatment.

M. Godfrin's house at Muno had been a 'transit camp' for more than twenty servicemen

at various times. He had spent the latter part of the war in Switzerland, after

the raid on his house. In 1947 my friends at Rulles presented me with part of

my parachute, and in 1981 my cap was returned to me by its finder, M. Burton,

a boy in 1943 living in Rulles.

Sadly, after more than forty years, many of these good friends have passed on.

Charles and Giny Spruyt, M. Godfrin, L'Abbé and his housekeeper;

Remi Goffin the gendarme, Doctor Wavreil of Tintigny, and no doubt others with

whom contact was lost, have since died. Monsieur Georges Quinot, a lawyer who

interrogated me at 'La Sapiniere' and provided my identity card died in

a concentration camp in Germany. Due to the indiscretions of a daughter, the

Beuré family of Fismes, were also taken to Germany, where presumably

they died.

Others, not known by name until many years later and who must not be omitted

from this narrative include the Roussel family (first house in Rulles); Armand

Zigueld (second house); Madame Keser (awarded honours for her Resistance work

and who gave me my first meal of plum pie), and Doctor Abbaye who examined me

for injury at Rulles. None will be forgotten.

Although we were never to meet, one more name must be added to those mentioned

above; that of Edgard Potier (his home was Florenville). He was an officer in

the Belgian Airforce, escaped to England, later to parachute back into Belgium.

He was instrumental in setting up the 'POSSUM' escape line. Betrayed to the

Gestapo, he committed suicide in 1944 after being horrendously tortured.

Top of page

Just before midnight on August 9th 1943, Lancaster W4236 'K' for King and dubbed

'King of the Air', was on course from base at Syerston near Newark, Nottinghamshire,

to Beachy Head and climbing to 18,000 feet on its last flight. The all-sergeant

crew, captained by pilot John Whitley and of which I was the wireless operator

was on its fifth mission, a raid on Mannheim in Southern Germany.

Just before midnight on August 9th 1943, Lancaster W4236 'K' for King and dubbed

'King of the Air', was on course from base at Syerston near Newark, Nottinghamshire,

to Beachy Head and climbing to 18,000 feet on its last flight. The all-sergeant

crew, captained by pilot John Whitley and of which I was the wireless operator

was on its fifth mission, a raid on Mannheim in Southern Germany. At about this time Luftwaffe Leutnant Norbert Pietrek with his crew, Unteroffizieren

(sergeants) Paul Gartig (wireless/radar operator) and Otto Scherer (engineer/gunner)

was taking off from the German night-fighter base at Florennes, Southern Belgium.

Their aircraft, a twin-engined Messerschmitt 110F-4 armed with four machine